Sulaiman Addonia Reimagines Brussels

When Sulaiman Addonia, the English-language author of Eritrean-Ethiopian descent, moved from London to Brussels, he felt thrown back into the time of Oliver Twist. But Addonia gradually changed, and with him his multi-layered view of the city.

When I first arrived in Brussels from London in 2009, I hated it. The ever-present feeling was one of gloom. I had this constant impression that I was in a city eternally surrounded by clouds, my mind like its buildings overcast. My walks, which are my way of alleviating mental pressure, yielded no release. Different areas of the city appeared to me an exact replica of each other, reproducing a repetitiveness that compounded my boredom. This was a city that shrouded itself in something so banal that it left me feeling utterly uninspired.

Now, though, and over a decade later, I am a lover of Brussels, so much that I, secretly, see myself as its poet laureate, because – even though I don’t write poems and never have done and probably never will – it is the feeling of being a poet, always in touch with my emotions, feelings and words, that accompanies me when I walk its streets day and night.

Sulaiman Addonia: 'Different areas of the city appeared to me an exact replica of each other.'

Sulaiman Addonia: 'Different areas of the city appeared to me an exact replica of each other.'© Divercity

Back to the Industrial Age

Since I became a writer in 2003, I started to look at and live everything through a writerly gaze. My relationships with people and the places I inhabit are ultimately defined through that prism. And what happened between the days I hated Brussels to how I feel about it now is a story that entirely took place in that writer’s mind.

London – with its streets, the Thames, canals, and parks – was at the heart of what inspired me to write my first book, and I wanted to find the same form of inspiration in Brussels when I arrived in 2009. Looking back, I think that I saw Brussels with a debut novelist’s eyes, eyes that were more easily enthralled by exteriors. Eyes that found easy satisfaction in a city like London, a city that was loud, brash, noisy, a city of skyscrapers made of bright glass that pierced through the clouds, a city permanently dressed up like a Michael Jackson’s sequins outfit, always on a night out, always on the dancefloor.

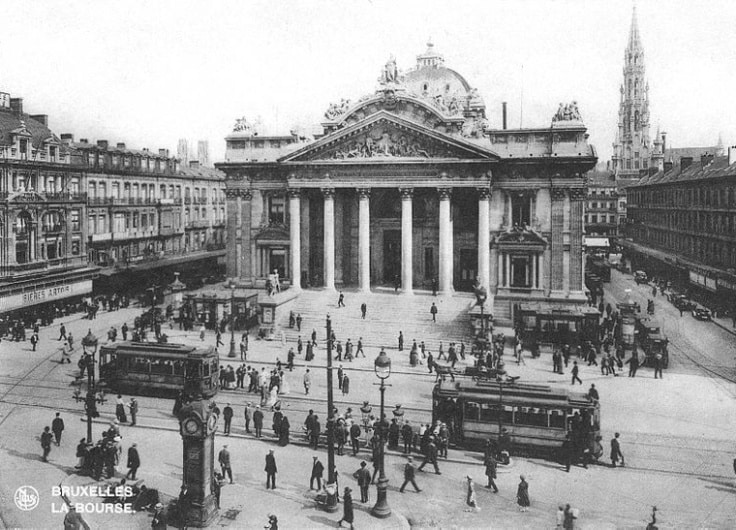

In contrast, Brussels seemed like a city rooted in the times of Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist. A city covered in the mystery of the Industrial Age.

Sulaiman Addonia: 'Brussels was the opposite of what I thought I needed at the time as a writer.'

Sulaiman Addonia: 'Brussels was the opposite of what I thought I needed at the time as a writer.'© Pexels / Petar Starčević

Indeed, Brussels was the opposite of what I thought I needed at the time as a writer. Then, I craved something easy to grasp, something that spoke to me immediately. Already overwhelmed with personal issues, I didn’t have the energy to lift the facade of a city and look under its layers for the things that made it beautiful and unique in order to get the inspiration I longed for. A city either had to show me something or it didn’t. The superficial was as deep as I could handle. That might be a harsh critique of myself and my capability as a person and artist at the time, but in all honesty, I was happy with the mundane in those days. A city that spoke a language of banality seemed more suited to my spirit then. That is not to say that London isn’t a profound city. It is. But unlike Brussels, it also has superficiality in abundance and that is satisfactory to those who want to bathe on the surface of their cities’ skins rather than to constantly having to dive deep to find those things they love about it.

Ways of feeling & seeing

I often associate the days before and after I fell in love with Brussels with my growth as a writer. Brussels hasn’t changed in that time. I have. And the way I looked at Brussels has changed, because I changed the way I saw things.

Studying John Berger’s theories outlined in The Ways of Seeing, and others like the Russian painter, Wassily Kandinsky, who emphasised the importance of “feelings” in art, I have come to understand the role I can play in reshaping the way I looked at things, including cities such as Brussels. Realising the power I had as a seer was a vital element in the puzzle of that relationship between Brussels and me to open up and become multilayered.

Sulaiman Addonia: 'The beauty of Brussels is in its depth, in its glamour hidden behind the grey facade.'

Sulaiman Addonia: 'The beauty of Brussels is in its depth, in its glamour hidden behind the grey facade.'© Pexels / Lexi Lauwers

I began to understand and appreciate Brussels when I learned to see it in a non-linear way, to observe it multidimensionally. I understood the need to have the patience for seeing a city like Brussels was necessary because its beauty was in its depth, in its glamour hidden behind the grey facade. But all that realisation came about when I let Brussels see me at my most vulnerable and creative, sombre and elated moments. The more I opened up to Brussels, and revealed many parts of me, the more it reciprocated.

By exposing my imagination to the wonder of letting go and entrusting my feelings to the city, I discovered that I was allowing for a humane-like exchange between Brussels and me to take place. Brussels was no longer a jungle city, made up of buildings, trees, roads, ponds, tunnels. But every part of those elements that make up Brussels started to have a soul, a history, a memory, a story. Brussels was a book. And a painting.

Brussels as a painting

I go to museums not to spend hours going from one room to another, but to spend hours in front of one single painting. When I took that obsessive attention to studying the detail of a painting to the streets of Brussels, the city started to appear utterly different than I had ever imagined it to be.

Dedicating as much time as possible to every part of the city, as if it was one painting, allowed me to see Brussels in minute detail. I would discover new elements on the same street even if I’d walked it a thousand times. And each detail and discovery provoked in me different feelings, different possibilities that touched different parts of my emotions and all that in turn allowed me to interpret the city in different ways. This was a city that could hold varieties of people, ethnicities, religions, languages in the same way its streets could effortlessly hold different architectural styles from modernism to art nouveau and brutalism.

We don’t just see cities, rather we feel cities, and we can reimagine cities as a reflection in our minds and state of being

I could reimagine the same street in different variations, as varied as the styles and thoughts and colours and origins as the people and buildings and plants living on that street.

That’s when it hit me. A city exists in reality but also as a reflection in our imaginations. This thought allowed me to view Brussels, not as a fixed entity but as something that constantly altered shape because of the role our observations and feelings play in shaping and reshaping the city when we look at it through our own specific lens.

This was a profound realisation for me and for my mental health of living in Brussels, a city I loathed for a long time. The truth was far more complex than I had realised. I now believed that I, as a citizen of Brussels, had the power to give birth to a different form of “Brussels” to call my own. That is to say that the realities and interpretations of my city change according to how I feel and how I see something at a particular time, a particular moment, a particular day, a particular month. That is to say that we don’t just see cities, rather we feel cities, and we can reimagine cities as a reflection in our minds and state of being.

Sulaiman Addonia: 'The city started to stir and provoke me from within each time I was out and about.'

Sulaiman Addonia: 'The city started to stir and provoke me from within each time I was out and about.'© Pixabay / Goi

Therefore, reimagining a city is not just the job of architects or city planners, but it is also dependent on our internal feelings. We, the citizens of a city, could give multiple rebirths to a city because of our ability to keep reinventing the way we see and feel it.

When I opened my feelings to Brussels and began to gradually see it beyond its concrete, cobblestones, tree-starved streets, it gained life in my head as a writer. The city started to stir and provoke me from within each time I was out and about, walking in Ixelles, the centre, Schaerbeek, or Forest.

A city that allows you to see yourself first and then see yourself reflected in its buildings and trees is an extension of your feelings, no matter how irrational that might seem. Such a city is the perfect place to write.